Catholic Persecution of Christian Saints in France

Chapter 5: Persecutions in France, Massacre of St. Bartholomew, and Revocation of the Edict of Nantes

29. We have already seen, in the massacres of the Waldenses of Beziers, Menerbe, Lavaur, and other places, that the emissaries of papal vengeance did not always wait for the slow process of inquisitorial examination and torture, to wreak their vengeance upon the detested heretics; and it would be easy to fill a volume with the horrid details of wholesale massacres of hundreds and thousands of heretics at the time, by which the faithful servants of the popes have merited and obtained from these self-styled successors of St. Peter, plenary indulgences, which should admit them, with their hands all reeking with blood, to the abodes of the blessed.

Omitting all mention of the horrid massacres of Orange and Vassy, in France [see Lorimer’s Protestant church of France, and Smedley’s Reformed Religion in France]; the butcheries of the bigoted duke of Alva, in the Netherlands, performed under the sanction of the husband of bloody Mary, Philip of Spain [for an account of the cruelties of the duke of Alva in the Netherlands, who testified that in six weeks he had caused 18,000 persons to be put to death for the crime of Protestantism, see Watson’s History of Philip II., book x.]; or the massacres in Ireland and other popish countries, we can describe but one which stands preeminent among these scenes of blood, viz, the massacre of St. Bartholomew, at Paris, on the 24th of August, 1572.

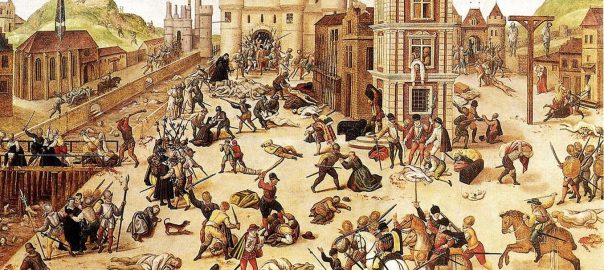

The massacre of St. Bartholomew was a plan laid by the infamous Catharine de Medici, queen dowager of France , in concert with her weak and bigoted son, Charles IX., for the extirpation of the French protestants, who were called by the name of Huguenots. Under the pretext of a marriage between Henry, the protestant king of Navarre , and Margaret, the sister of Charles, the Huguenots. with their most celebrated and favorite leader, admiral Coligny, had been attracted to Paris . Coligny had been affectionately warned by many of his friends against trusting himself at Paris , but such were the assurances of friendship on the part of king Charles, that he was thrown off his guard, and was drawn within the toils that popish malignity and craft had laid for him. On the 22d of August, an attempt was made to assassinate the Admiral by a shot fired at him in the street, by which he was wounded in the arm. This act was doubtless perpetrated at the instigation of the infamous queen mother, if not of her son, though that wicked woman pretended deep commiseration, and upon a visit to the Admiral remarked, that she “did not believe now the King could sleep safely in his palace.” And yet both the mother and son, were at that very moment, and had for weeks past been deliberately concocting a plan for the slaughter not only of Coligny, but of all his protestant friends, whom they had now caught in their toils at Paris; and in all this, no doubt, their popish bigotry taught them they were doing God service!

30. At length the fatal hour had arrived. All things were ready. The tocsin, at midnight , tolled the signal of destruction. The troops were sent forth, by royal command, to perform their work of death. The assassins rushed into Coligny’s hotel, killing several protestant Swiss soldiers as they passed. “Save yourselves, my friends,” cried the generous-minded chief. “I have long been prepared for death.” They obeyed his commands, and escaped through the tiling of the roof; and in a moment after, the daggers of the popish assassins

were buried in the heart of the noble chief of the protestants, and his body ignominiously thrown from the window, to be exposed to the rude insults of the bigoted populace. Among those who escaped through the tiling was a protestant clergyman, M. Merlin, the chaplain of the Admiral. His escape was attended with a remarkable providential circumstance. He hid himself in a hayloft, where he was sustained for three days by an egg each day, which a hen laid, for his support.

After the death of Coligny, the slaughter soon extended itself to every quarter of the city, and when the glorious sun looked forth that morning, it was upon an awful spectacle. The dead and the dying mingled together in undistinguished heaps. The pavements besmeared with a path of gore, along which the bodies of the murdered protestants had been dragged to be cast into the waters of the Seine , already dyed with the blood of the slain. The executioners rushing through the streets, bespattered with blood and brains, brandishing their murderous weapons, and in merriment, mimicking the psalm-singing of the protestants! The frantic Huguenots, bewildered with fright, running hither and thither to seek a place of safety, but in vain. Some ran towards the house of Coligny, but only to fall by the hands of the same murderers; others, remembering the solemn promises of the King, and hoping that he was not privy to the massacre, ran toward the palace of the Louvre, but only to meet a more certain and speedy death; for, even Charles himself fired upon the fugitives from the window of the palace, shouting with the fiend-like fury of a devil or an inquisitor, “KILL THEM! KILL THEM!” The Louvre itself was a frightful scene of slaughter. The protestants who had remained there, in the train of the king of Navarre , were called out one by one, and put to death in cold blood, under the very eyes of the king. Even the protestant king of Navarre himself had been ushered into the presence of Charles through long lines of soldiers thirsting for his blood, and commanded with oaths to renounce the protestant faith, and was then, together with the prince of Conde, thrust into prison, and informed that unless they embraced the Roman Catholic faith in three days, they would he executed for treason. In the meanwhile the work of slaughter went forward, and during seven days, at the lowest computation, 5,000 protestants were murdered in the city of Paris alone. [That of Mezeray. Boussuet says 6000, and Davila 10,000 victims in Paris .]

31. The whole city was one great butchery and flowed with human blood. The court was heaped with the slain, on which the King and Queen gazed, not with horror, but with delight. Her majesty unblushingly feasted her eyes on the spectacle of thousands of men, exposed naked, and lying wounded and frightful in the pale livery of death. The king went to see the body of admiral Coligny, which was dragged by the populace through the streets; and remarked, in unfeeling witticism, that the “smell of a dead enemy was agreeable.”

The tragedy was not confined to Paris, but extended, in general through the French nation. Special messengers were, on the preceding day, dispatched in all directions, ordering a general massacre of the Huguenots. The carnage, in consequence, was made through nearly all the provinces, and especially in Meaux, Troyes, Orleans, Nevers, Lyons, Thoulouse, Bordeaux, and Ronen. Twenty-five or thirty thousand, according to Mezeray, perished in different places. Many were thrown into the rivers, which, floating the corpses on the waves, carried horror and infection to all the country, which they watered with their streams. The populace, tutored by the priesthood, accounted themselves, in shedding heretical blood, “the agents of Divine justice,” and engaged “in doing God service.” The King, accompanied with the Queen and princes of the blood, and all the French court, went to the Parliament, and acknowledged that all these sanguinary transactions were done by his authority. “The Parliament publicly eulogized the King’s wisdom,” which had effected the effusion of so much heretical blood. His Majesty also went to mass, and returned solemn thanks to God for the glorious victory obtained over heresy. He ordered medals to be coined to perpetuate its memory. A medal accordingly was struck for the purpose with this inscription, PIETY EXCITED JUSTICE.

32. The King sent a special messenger to the Pope to announce to him the joyful intelligence of the extirpation of the protestants, and to tel

l him that “the Seine flowed on more majestically after receiving the dead bodies of the heretics.” Nothing could exceed the joy with which the news was received at Rome. The Pope and cardinals went in procession to the church of St. Louis to return solemn thanks to God (oh, horrible impiety!) for the extirpation of the heretics. Te Deum was sung, and the firing of cannon announced the welcome news to the neighborhood around. The Pope’s legate in France felicitated his most Christian majesty in the Pontiff’s name, “and praised the exploit, so long meditated and so happily executed, for the good of religion.” The massacre, says Mezeray, “was extolled before the King as the triumph of the church.”

The Pope was not satisfied with a temporary expression of his joy. He caused a more enduring memorial to be struck in the form of triumphant medals in commemoration and honor of the event. These medals represented on one side an angel carrying a sword in one hand, and a crucifix in the other, employed in the slaughter of a group of heretics, with the words HUGONOTORUM STRAGES (slaughter of the Huguenots), 1572; on the other side, the name and title of the reigning Pope. A new issue of this celebrated medal in honor of the Bartholomew massacre has recently been struck from the papal mint at Rome, and sold for the profit of the papal government.

Such was the joy of the cardinal of Lorraine (whom we have already seen closing the council of Trent with anathemas against heretics), upon receiving the news at Rome, that he presented the messenger with one thousand pieces of gold and unable to restrain the extravagance of his delight, exclaimed aloud that “he believed the King’s heart must have been filled with a sudden inspiration from God when he gave orders for the slaughter of the heretics.” Another Cardinal, Santorio, afterwards pope Clement VIII., in his autobiography, designates the massacre as “the celebrated day of St. Bartholomew, most cheering to the Catholics.” [He speaks of the “giusto sdegno del rer Carlos IX. di gloriosa memoria, in quel celebre giorno di S. Bartolomeo lietissimo a’ cattolici;” that is, “the just wrath of king Charles IX., of glorious memory, on the celebrated day of St. Bartholomew, most cheering to catholics.” (Cited by Ranke in his History of the Popes, book vi., p. 228.)] Thus is it by the joy of the Pope and cardinals at the massacre, by the medal struck in its commemoration and honor, and by their solemn thanksgivings for the happy events, without alluding to the proofs (by no means inconsiderable) of a previous correspondence between the Pope and the King, that this horrible slaughter is fixed as another dark and damning spot upon the blood-stained escutcheon of Rome.

33. After the massacre of Bartholomew, the protestants of France continued to be the subjects of cruel and bitter persecution from the papists, and yet in the midst of all, the blood of the martyrs was the seed of the church, and the cause of God and of truth continued steadily to advance.

At length, in the year 1598, twenty-six years after the massacre, an edict granting the protestants liberty of worship, with certain restrictions, was passed, through the favor of king Henry IV. This was called the edict of Nantes, and though far from removing all disabilities on account of religion, was received by the protestants with joy and gratitude. It continued in force till 1685, though for the last few years of that period many of its provisions had been violated with impunity, and the protestants exposed to a series of cruel insults and annoyances from their popish neighbors.

In the year 1685, king Louis XIV. of France, a bigoted papist, at the persuasions of La Chaise, his Jesuit confessor, publicly revoked that protecting edict, and thus let loose the floodgates of popish cruelty upon the defenceless protestants. By the edict of revocation, all former edicts protecting the protestants were fully repealed ; they were forbidden to assemble for religious worship; all their ministers were banished the kingdom within fifteen days under penalty of being sent to the galleys;* all their children born in future were ordered to be brought up in the Roman Catholic religion, and the parents required to send them to the popish churches under a penalty of five hundred livres; and what rendered the law yet more cruel, all other protestants, except the banished ministers, were forbidden to depart out of the kingdom, under penalty of the galleys for men, and of confiscation of money and goods for the women.

[* Sent to the galleys.-This was a punishment somewhat similar to sending felons to the hulks or convict ships, such as those at Woolwich, England; except that the rigor of the former was much greater. The galley-slave was chained to his oar, compelled to labor without intermission, in company with the vilest felons and blasphemers, and continually exposed to the lash of the cruel and (in the case of heretics especially) often vindictive taskmaster, upon his naked back. To this horrid and degrading punishment, some of the most distinguished and learned of the French protestant clergy were doomed during this persecution.]

34. In the cruelties that followed the revocation of the edict of Nantes, the policy of Rome appeared to be changed. She had tried, in innumerable instances, the effect of persecution unto death, and the results of Bartholomew had shown that it was not effectual in eradicating the heresy. Now, her plan was by torture, annoyance, and inductions of various kinds suggested by a brutal ingenuity, “to wear out the saints of the Most High.” One of the most common means was what was called dragoonading; that is quartering brutal dragoons upon the defenceless people, who had license to employ any means in their power to compel the poor persecuted protestants to embrace the popish faith. “There was no wickedness,” says M. Quick in his Synodicon, “though ever so horrid, which they did not put in practice, that they might enforce them to change their religion. Amidst a thousand hideous cries and blasphemies, they hung up men and women by the hair or feet upon the roofs of the chambers, or hooks of chimneys, and smoked them with wisps of wet hay till they were no longer able to bear it; and when they had taken them down, if they would not sign an abjuration of their pretended heresies, they then trussed them up again immediately. Some they threw into great fires, kindled on purpose, and would not take them out till they were half roasted. They tied ropes under their arms, and plunged them again and again into deep wells, from whence they would not draw them till they had promised to change their religion. They bound them as criminals are when they are put to the rack, and in that posture, putting a funnel into their mouths, they poured wine down their throats till its fumes had deprived them of their reason, and they had in that condition made them consent to become Catholics. Some they stripped stark naked, and after they had offered them a thousand indignities, they stuck them with pins from head to foot; they cut them with penknives, tore them by the noses with red-hot pincers, and dragged them about the rooms till they promised to become Roman Catholics, or till the doleful cries of these poor tormented creatures, calling upon God for mercy, constrained them to let them go.

They beat them with staves, and dragged them all bruised to the popish churches, where their enforced presence is reputed for an abjuration. They kept them waking seven or eight days together, relieving one another by turns, that they might not get a wink of sleep or rest. In case they began to nod, they threw buckets of water in their faces, or holding kettles over their heads, they beat on them with such a continual noise, that those poor wretches lost their senses. If they found any sick, who kept their beds, men or women, be it of fevers or other diseases, they were so cruel as to beat up an alarm with twelve drums about their beds for a whole week together, without intermission, till they had promised to change. In some places they tied fathers and husbands to the bedposts, and ravished their wives and daughters before their eyes. And in other places rapes were publicly and generally permitted for many hours together. From others they plucked off the nails of their hands and toes, which must needs have caused an intolerable pain.”

35. The galleys formed another mode of oppression. There, a vast body of protestants, some of them, such as Marolles and Le Febvre, of the highest station and talent, were confined-wretchedly fed on disgusting fare-and wrought in chains for many years. The prisoners often died under their sufferings. When they did not acquit themselves to the mind of their taskmasters, or disregarded any of their persecuting enactments, they were subjected to the lash. Fifty or sixty lashes were considered a punishment severe enough for the criminals of France-men who were notorious for every species of profligacy; but nothing less than one hundred to one hundred and fifty would suffice for the meek and holy saints of God. They were considered a thousand times worse than the worst criminals.

It is a striking feature of the persecutions of Popery that the more holy and Christ-like her victims, the more dreadfully severe have been the character of their sufferings; her war has not been against wickedness, but heresy, and she could readily tolerate the grossest immorality, so long as she had no reason to complain of the rejection of her creed.

This is consistent with her true character. Popery is ANTI-CHRIST, and it is natural to suppose that the nearer men come to the character of Christ, the fiercer will be her hatred, and the more bitter her persecution. Hence the quenchless enmity of Rome for such holy men as Wickliff and Huss and Jerome, Rogers and Latimer and Ridley, Le Febvre and Marolles and Mauru. We shall present an extract or two from the letters of the three last named victims of the revocation of the edict of Nantes, while suffering under the cruel inductions of the papal anti-Christ, to sustain this assertion.

36. Says Le Febvre, when writing from a noisome dungeon, “Nothing can exceed the cruelty of the treatment I receive. The weaker I become, the more they endeavor to aggravate the miseries of the prison. For several weeks no one has been allowed to enter my dungeon; and if one spot could be found where the air was more infected than another, I was placed there. Yet the love of the truth prevails in my soul; for God, who knows my heart, and the purity of my motives, supports me by his grace. He fights against me, but he also fights for me. My weapons are tears and prayers. The place is very dark and damp. The air is noisome, and has a bad smell. Everything rots and becomes mouldy. The wells and cisterns are above me. I have never seen a fire here, except the flame of the candle. You will feel for me in this misery,” said he to a dear relative, to whom he was describing his sad condition: “but think of the eternal weight of glory which will follow. Death is nothing. Christ has vanquished the foe for me: and when the fit time shall arrive, the Lord will give me strength to tear off the mask which that last enemy wears in great afflictions. . . . Far be it from me to murmur. I pray without ceasing, that he would show pity, not only to those who suffer, but also to those who are the cause of our sufferings. He who commanded us to love our enemies, produces in our hearts the love he has commanded. The world has long regarded us as tottering walls, but they do not see the Almighty hand by which we are upheld.”

37. Says Marolles, a minister of eminent piety, and extensive scientific attainments, in a letter to his wife, after being removed from a galley to a dungeon, “When I was taken out of the galley and brought hither, I found the change very agreeable at first. My ear’s were no longer offended with the horrid and blasphemous sounds with which those places continually echo. I had liberty to sing the praises of God at all times, and could prostrate myself before him as often as I pleased. Besides, I was released from that uneasy chain, which was far more troublesome to me than the one of thirty pounds weight which you saw me wear.” He then goes on to speak of a temptation into which he was permitted to fall- a distrust of God lest he should lose his reason, and a fear that he was advancing to a state of insanity- “At length many prayers, sighs, and tears, the God of my deliverance heard my petitions, commanded a perfect calm, and dissipated all those illusions which had, so troubled my soul. After the Lord has delivered me out of so sore a trial, never have any doubt, my dear wife, that he will deliver me out of all others. Do not, therefore, disquiet yourself any more about me. Hope always in the goodness of God, and your hope shall not be in vain. I ought not, in my opinion, to pass by unnoticed a considerable circumstance which tends to the glory of God. The duration of so great a temptation was, in my opinion, the proper time for the Old Serpent to endeavor to cast me into rebellion and infidelity; but God always kept him in so profound a silence, that he never once offered to infest me with any of his pernicious counsels; and I never felt the least inclination to revolt. Ever since those sorrowful days, God has continually filled my heart with joy. I possess my soul in patience. He makes the days of my affliction speedily pass away. I have no sooner begun them than I find myself at the end. With the bread and water of affliction he affords me continually most delicious repasts.” This was his last letter. He resigned his spirit into the hands of his heavenly Father on the 17th June, 1692.

38. The next example of suffering piety, from whom I shall quote, was of one who wrote from amidst the slavery and suffering and horrors of the galleys. Says Pierre Mauru, after referring to the cruel stripes he was forced to bear, from twenty to forty at a time, and these repeated frequently for several days in succession. “But I must tell you, that though these stripes are painful, the joy of suffering for Christ gives ease to every wound; and when, after we have suffered for him, the consolations of Christ abound in us by the Holy Spirit, the Comforter: they are a heavenly balm, which heals all our sorrows, and even imparts such perfect health to our souls, that we can despise every other thing. In short, when we belong to God, nothing can pluck us out of his hand. If my body was tortured during the day, my soul rejoiced exceedingly in God my Saviour, both day and night. At this period especially, my soul was fed with hidden manna, and I tasted of that joy which the world knows not of; and daily, with the holy apostles, my heart leaped with joy that I was counted worthy to suffer for my Saviour’s sake, who poured such consolations into my soul that I was filled with holy transport, and, as it were, carried out of myself. But this season of quiet was of short duration; for soon afterwards the galley was furnished with oars to exercise the newcomers; and then these inexorable haters of our blessed religion took the opportunity to beat me as often as they pleased, telling me it was in my power to avoid these torments. But when they held this language, my Saviour revealed to my soul the agonies he suffered to purchase my salvation, and that it became me thus to suffer with him.

After this, we were ordered to sea, when the excessive toil of rowing, and the blows I received, often brought me to time brink of the grave. Whenever the chaplain saw me sinking with fatigue, he beset me with temptations; but my soul was bound for the heavenly shore, and he gained nothing from my answers. In every voyage there were many persons whose greatest amusement was to see me incessantly beaten, but particularly the captain’s steward, who called it painting Calvin’s back, and insultingly asked if Calvin gave me strength to work after being so finely bruised; and when he wished the beating to be repeated, he would ask if Calvin was not to have his portion again. When he saw me sinking from day to day under cruelties and fatigue, his happiness was complete. The officers, who were anxious to please him, had recourse to this inhuman sport for his entertainment, during which he was constantly convulsed with laughter. When he saw me raise my eyes to heaven, he said, ‘God does not hear Calvinists when they pray. They must endure their tortures till they die, or change their religion.

. . . . In short, my very dear brother, there was not a single day, when we were at sea, and toiling at the oar, but I was brought into a dying state. The poor wretched creatures who were near me did everything in their power to help me, and to make me take a little nourishment. But in the depth of distress, which nature could hardly endure, my God left me not without support. In a short time all will be over, and I shall forget all my sorrows in the joy of being ever with the Lord. Indeed, whenever I was left in peace a little while, and was able to meditate on the words of eternal life, I was perfectly happy; and when I looked at my wounded body, I said, here are the glorious marks which St. Paul rejoiced to bear in his body. After every voyage I fell sick; and then, being free from hard labor and the fear of blows, I could meditate in quiet, and render thanks to God for sustaining me by his goodness, and strengthening me by his good Spirit.”

HERE IS THE FAITH AND THE PATIENCE or THE SAINTS. Is it possible to conceive of suffering borne in a holier cause or in a more Christ-like spirit?

39. It would be an endless task to recount all the inventions of popish ingenuity to harass and to wear out these saints of the Most High. One which could not have been conceived anywhere else but in the bottomless pit and in the heart of a fiend, deserves to be mentioned. On January 23d, 1685, a woman had her sucking child snatched front her breasts, and put into the next room, which was only parted by a few boards from her’s.

These devils incarnate would not let the poor mother come to her child, unless she would renounce her religion and become a Roman Catholic. Her child cries and she cries; her bowels yearn upon the poor miserable infant; but the fear of God, and of losing her soul, keep her from apostasy. However she suffers a double martyrdom, one in her own person, the other in that of her sweet babe, who dies in her hearing with crying and famine before its poor mother. The heart sickens at the contemplation of such enormities. Human language cannot describe the sufferings of these oppressed victims of popish cruelty. It is only the Spirit of God who can mark the terrible lineaments, and he does so when he speaks of “wearing out the saints of’ the Most High,” and of anti-Christ being “drunk with the blood of the saints,” and of their blood crying from under the altar, “O Lord, holy and true, how long dust thou not judge and avenge our blood upon them that dwell on the earth?” and when he speaks of similar worthies as persons “who were stoned, were sawn asunder, were tempted, were slain with the sword: they wandered about in sheep-skins and goat-skins, being destitute, afflicted, tormented (of whom the world was not worthy): they wandered in deserts and in mountains, and in dens and caves of the earth.”

40. Let the reader carefully consider the above affecting and authentic instances of suffering for Christ’s sake, and then let him read the following language of Pope Innocent XI., in praise of the popish bigot, by whose orders they were inflicted. This Pontiff wrote a splendid letter to king Louis, expressly thanking him in the warmest and most glowing terms for the service he had rendered the church in his persecuting edict against the heretics of France. The Pope requests him to consider this letter a special testimony to his merits, and concludes it in the following words: “The Catholic Church shall most assuredly record in her sacred annals a mark of such devotion toward her, AND CELEBRATE YOUR NAME WITH NEVER-DYING PRAISES; but, above all, you may most assuredly promise to yourself AN AMPLE RETRIBUTION from the divine goodness for this most excellent undertaking, and may rest assured that we shall never cease to pour forth our most earnest prayers to that Divine goodness for this intent and purpose.” [Lorimer’s Protestant Church of France, chap. iv.]

Thus evident is it not only that the acknowledged head of the apostate church of Rome approved of the horrid barbarities inflicted upon the French protestants, but that he regarded their perpetrator as conferring a special favor upon that church, thus entitling himself to her lasting gratitude and her warmest thanks.